A brief history of the Congregation of the Augustinians of the Assumption

A brief history of the Congregation of the Augustinians of the Assumption

In 1845, at the heart of a century that saw the birth of many new religious congregations, Emmanuel d’Alzon founded the Augustinians of the Assumption (Assomptionists). This man of strong character wanted a “modern congregation” to renew the Catholic spirit in society. Marked by the divisions that prevailed in the world, Father d’Alzon worked to promote unity and reconciliation.

With his first religious brothers, he committed himself to education, taking charge of the Collège de l’Assomption in Nîmes. He wanted youth to transform society through social engagement as much as through spreading the Good News. Concerned with defending the “Catholic truth,” Emmanuel d’Alzon also turned toward the East. Encouraged by Pope Pius IX, he sent religious to Bulgaria and Turkey.

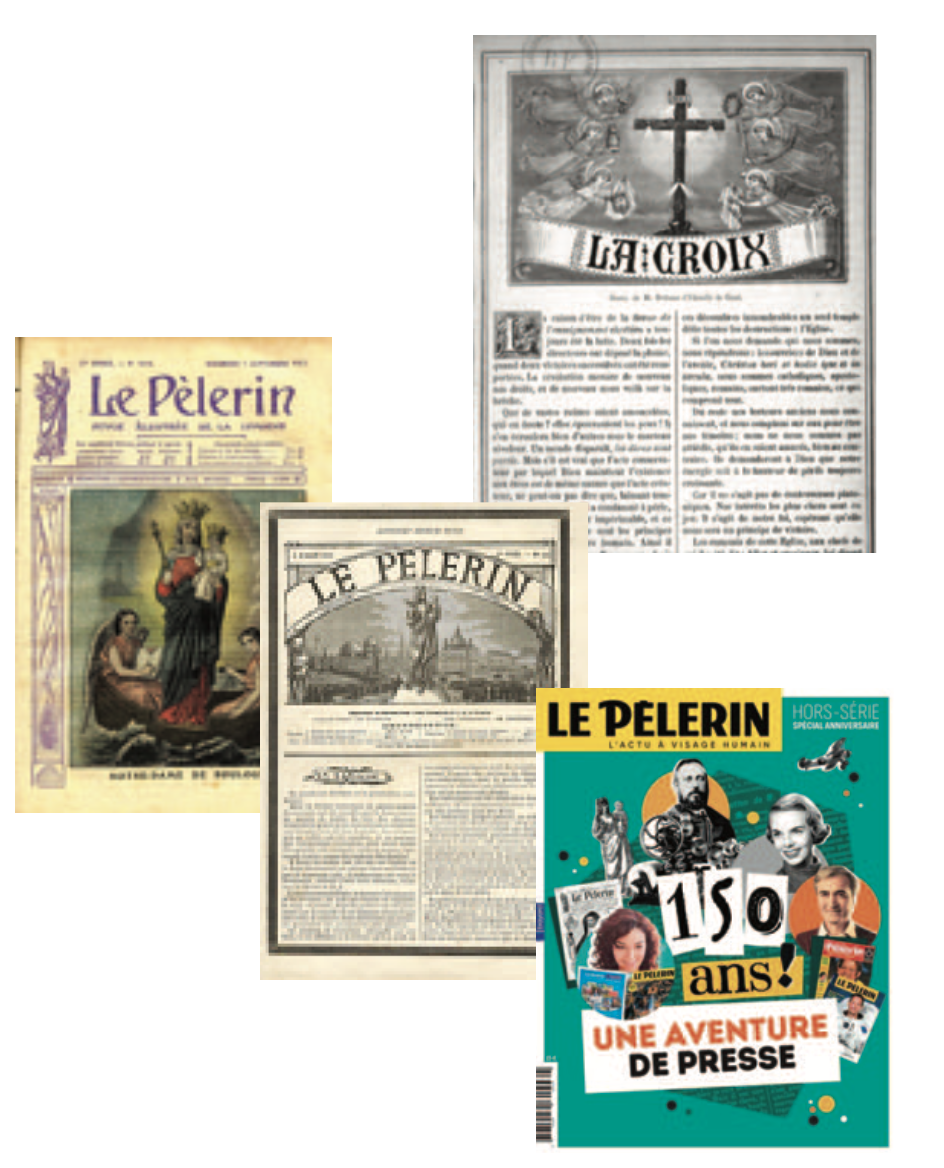

Another pillar of the Assumption’s apostolate was the creation of the “Bonne Presse,” now known as Bayard Presse — a work to promote Christian spirit and contribute to the formation of men and women of our time.

At the Founder’s death in 1880, the congregation had 68 religious and 11 novices. It was after his death that the congregation saw significant growth. Alumnates — small seminaries for young men from modest families — provided the majority of vocations to the Assumption. By the mid-20th century, the congregation reached a peak of nearly 2,000 religious.

Father François Picard, who succeeded Father d’Alzon, contributed significantly to the growth of the congregation’s major works. At La Bonne Presse, he was involved with Le Pèlerin (founded in 1873) and La Croix, which became a daily newspaper in 1883. In the following quarter-century, more than 30 publication titles were launched.

There were also pilgrimages to Lourdes, Rome, and Jerusalem, where the Assumptionists accompanied large groups of pilgrims. The Mission of the East, which began in Bulgaria and Turkey, expanded to Russia, Romania, and beyond.

Finally, the foundation of Collège Saint-Augustin in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, became a new highlight in the congregation’s educational mission.

In France, the Third Republic was particularly anti-clerical. Starting in 1880, religious were expelled from their communities. In 1900, the congregation was dissolved and the Assumptionists were expelled from France. They were likely targeted due to the significant influence of their press organs, especially La Croix. However, as was the case for other French congregations, this persecution contributed to the international expansion of the Assumptionists, in Europe, South America, and North America.

Under Father Emmanuel Bailly (from the beginning of the 20th century until the end of World War I), the congregation faced the double hardship of dispersion and war. This included the dismantling of communities and works in Turkey and Bulgaria (where before the war there were up to 150 religious and 200 Oblate Sisters of the Assumption) as well as the death of many young religious on battlefields, and the looting or confiscation of property in several countries.

However, the war also had a positive effect for the Assumptionists. Religious who had fulfilled their military duty in France were allowed to remain there. Yet, for various reasons, the congregation only received official recognition by the French State in 2013 — 168 years after its foundation!

From the end of World War I to the Second Vatican Council, the Assumption experienced years of expansion and missionary adventure (with, of course, the interruption of World War II): a renewed presence in the Mission of the East; foundations in the Belgian Congo, North Africa, China, Madagascar, and West Africa... It was also a time of persecution in the Soviet bloc countries... Several religious were deported to forced labor camps, and three of them, recognized as martyrs of the faith, were sentenced to death in 1952 in Bulgaria.

This period also saw the growth of Augustinian Studies and Byzantine Studies, with specialized libraries, scholarly journals, and Assumptionist researchers who became leading figures and experts on Augustine and the Byzantine world.

The post-Conciliar period was a time of trial, with many departures, but also a time of renewal that led, in the 1980s, to a return to the fundamental Augustinian and Alzonian orientations and a revitalization of youth ministry and vocations.

Finally, the 2000s were marked by development in Asia, a return to West Africa, and a much more international dynamic within the congregation.